I remember holding the Star Walk app up to the sky and loving every part of what I was seeing — the stars formed 3D shapes, and names of stars and constellations appeared as if I was holding the Marauder’s map of the universe in front of my eyes. But that feeling of bliss left my body once I started lowering my cellphone to the horizon, when, what I thought of as the underneath — the steady earth — showed on the screen as water, and below water just as space, as if I were floating and there was no actual solid matter under my feet. I quickly put it down and deleted it. (I downloaded the app again to write this intro, and I had to put it away yet again.)

I figured my fear of space had something to do with how I related to my ego because by putting the app away, it became evident that I couldn’t stand the fact that being ‘grounded’ is just a notion — that I’m one little thing on one side of the earth, which is opposite to a deep ocean on the other side, and its depth is closer to me than its surface, which is itself moving, and by moving in circles, we both share the same stars, the moon, the sun.

Physicist Carlo Rovelli explores this innate fear we have towards the unknown. In his book The Order of Time, apart from explaining entropy and the relativity of time, he dwells with the idea of ‘one perspective’ and writes about it nebulously, as if sewing it softly through and between the lines. It seems like most of the notions he deconstructs are blurry subjects even for himself as a physicist but he makes it clear that the smartest way to go, is to accept chaos as a pillar of existence — to know that nothing is linear nor logical.

While reading about how ‘our interaction with the world is partial, which is why we see it in a blurred way’, I felt a certain amount of peace I hadn’t felt in a while, or ever, in fact. Anything will look blurry within our human capacities, and regardless of how far away we travel from earth or from ourselves, our history is a tiny piece in a thousand other things happening at this moment, and our only way to live it is partially and out of focus (and I mean this in both an individual and a collective way). Our idea of a reflection is therefore another belief we’ve made up, as the basis for it calls for a division between ourselves and the rest of the world, when in reality, we’re part of it.

So, to put it simply, I put away the app because I was afraid of seeing things I’m not built to see nor truly comprehend — vastness is difficult to grasp.

On a daily basis though, I try to remind myself that ‘the more you know, the less you fear’, a phrase I can see anywhere on Instagram; a phrase most math teachers should have used on me. I heard it from Chris Hadfield though, at age 29. Hadfield is the man who spent 166 days in space, and the same man who was blind in space while he was spacewalking. In his TED talk, Hadfield compares danger vs. fear by using a spider as an example of things we fear generically, but not out of real danger necessarily: ‘…if you walk through a hundred spider webs you will have changed your fundamental human behaviour’. That there is his answer to tackling an irrational fear — the way he tackled his own (very rational) fear of something going wrong in space. Essentially, he means that our rawest behaviour to fear things is normal, but that it can be hacked by confronting it.

I can’t go to space a hundred times in order to get over my fear of space, but I can, in turn, humanise the idea of vastness, which is what we’ve done as a species with everything that seems too big for us to understand as truth; we have put the history of our home into narratives and timelines we believe in and force others to believe, unaware of how many possible realities we might be ignoring by telling one single story. Yet we have also sent rockets outside of earth, we have landed on the moon, we have pushed the boundaries of our own eyes, and through telescopes, we have managed to look 13.300.000.000 years back in time.

I interrupted Camilo’s flow as he told me the exact number of years. ‘How many again?’. I usually can’t imagine the size of a city by numbers for example. If you tell me your city has a million people I might think it’s the same amount of people walking through a local mall right at this moment. ‘13.300.000.000, and we’re only missing another 400.000 to go back to the big bang’.

Camilo is a space lawyer, but the first time I heard of him I thought he was a ‘star lawyer’, picturing him defending Lindsey Lohan from yet another scandal with a paparazzi. He tells me that most people never really understand what his job entails — most think he is a lawyer of actual space on earth. I figure he is the perfect person for me to talk to — law being the most innovative human concept for protecting and controlling our ‘natural’ tendencies towards violent behaviour, intrinsically helping us be less feral and more civilised — whatever that might mean out there in space.

He begins by telling me that his job is to keep legal issues in space at bay and that some rules, even if similar to those on earth, are far more complicated because of a lack of a sense of ownership in space — opposite to what happens here, where every nook is delimited and owned (well, apart from Antarctica). Yet the problems he’s anticipating don’t regard physical ownership as I had thought, but those arising from an upcoming interest in space exploration veering away from a scientific approach, and into an economic one.

I personally prefer the romance of looking at a star and knowing that I’m staring at the past, or that the moon is something you give someone as a metaphoric gift when you’re 15 and in love. Insidiously, as good modern humans, we’re leaving the poetry to the side to reconsider how it is that we’re going to get the most resources out of extraterrestrial objects. Camilo corrects me when I say that it isn’t surprising to me that we’re about to suck out the little life left on Mars. ‘No, mining on Mars would be equally difficult as it is on earth. I meant asteroid mining.’

So, Armageddon wasn’t too far away from reality. I have known it since I was 9 and in love with Ben Affleck. I don’t tell him about what runs through my mind the moment he mentions asteroid mining, but I do suggest Star Wars could eventually happen, guiding myself by the title, not having watched any of the films. ‘Oddly enough, the working environment related to space has been and still is, very healthy and friendly between countries and private companies, and militarisation in space is not allowed, so no space cowboys for us,’ he answers, to my surprise. I never worried about space stations serving as military stations, but I did imagine the equivalent of a Mark Zuckerberg at NASA — since there has been an air of competition between countries in the past, like when the United States managed to land on the moon before Russia (and went into enormous debt to make it there first); or when China shot a rocket just to prove that they could destroy their own satellites. Ego, from my perspective, is always involved.

Regardless of my despiteful comments about not believing in our human race as a civilised one, Camilo assures me that it has been indeed very peaceful — mainly because of an inevitable interdependence in every aspect involved: research, money, satellite information — everything starts making more sense. Already knowing where their decency is coming from, I ask him again if he thinks the existence of space organisations comes from an innate drive for survival as a species, or if it comes mainly from the human ego.

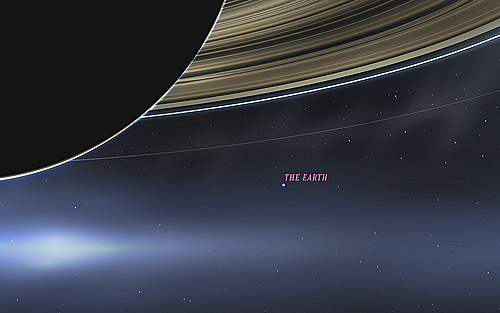

‘At the beginning, an idea of reaching somewhere might come from our ego, but those who go up there successfully or manage to send a camera and take a photograph of something we’ve never seen, are faced with two things: their target, but also an immense vastness of nothingness around it and beyond. It’s a feeling similar to seeing something with a telephoto lens and not being able to touch it. So knowing about something, but not being able to research it to its core, inevitably awakens a drive for survival. Getting to that point of understanding that you, up there, have reached something big and unthinkable for our race, but that in comparison to the history of the universe it means nothing, gives you a perspective different from that you have on earth. Every delimited space, every boundary disappears because you begin to understand that you’re not even a tiny bit of sand on a vast beach.’

By this point in our conversation, I begin feeling less pressure in my belly, and a whole lot of expansion in my chest. Like I am part of a breathing organism and not ‘on’ it, or ‘living in it’, and that it is fine to float. I tell Camilo that while doing research, I came upon a photograph taken by the Cassini spaceship on July 19th, 2013 — often referred to as ‘the day the earth smiled’. I felt the same rollercoaster fall in my body that I felt with the app, but this time, a whole new perspective of seeing the earth and the moon hanging somewhere (nowhere) gave me peace. It is still one perspective, but this one deconstructs and reconstructs any idea I had about the self and ‘the other’.

The notion of ‘the other’ has permeated our belief system and is the premise for every story. In terms of the appearance of ideas such as money, religion, and politics in our society, a new sense of ownership was needed to give each of those concepts the means to expand — a sense that intrinsically called for the conceptualisation of identity — that which divided theirs from ours.

It is funny that the result of that adjustment brought us to taking our identity away from that of nature, forgetting the fact that we are built like conjoined twins with one beating heart. But what is changing if we’re redefining space, and moving towards an economical relationship with it? How is our collective identity potentially changing? What will ours mean? Will we create a story where the new Adam and Eve will be given (nature) in space for personal use? Will we still be at the top of the food chain for having built spaceships?

Our society is somewhere there in adolescence — a liminal time where gathering stuff and using our power to own is our top priority. But I wonder if spacewalks and telescopic photographs can somehow be of help to our egos, our fears, and our limitations, or if it will make us Adam and Eve yet again. ‘We are born out of a thousand twists and natural coincidences, of explosions, of destruction. Of being at the exact needed distance from the sun. We are alive because of gravity. And even though it all seems to be telling us that we were meant to be, we are in fact inconsequential. In another 13.000.000 years, there might be another civilisation that believes they’re the chosen ones by God because our tendency is to believe that we matter.’ I stop to let that sink in for a second but Camilo continues to say that ‘telling people they’re inconsequential doesn’t sell’. ‘When we finally found that there had been water on Mars, people focused on finding human-like figures on the photographs, as if craving to find a reflection of themselves out there — as if the only form of life important enough for a front-page is one like ours.’

While writing this, I begin to understand that my fear of space is just an analogy of the rest of the fears I carry, and those we carry, innately, as human beings. Most of the phobias are connected to ‘not knowing’, ‘thinking what the other might think’, or ‘not being able to escape’, but if we stop for a second and look into space, we might realise that we won’t find a ‘reflection’ but that we are part of the full image, of a moving organism, and that there’s nothing to escape from. Anything moving is hard to catch. Anything moving lacks an outline. And that’s a good beginning to not only freeing ourselves from those stories we have chosen to tell ourselves but in changing the tendency to believing in one single narrative, even when it’s our own.

So, where does that fall in a line of perspective? Well, objectivity is born out of very deep subjectivity and every cycle and movement that nature entails is just as far as we can go in both directions. And as we go, collectively, in our travels to find a less blurry image of our home — and while protecting our process in getting there —, we begin to understand that there is no ownership, no above or below, no steadiness; that vastness in all directions can bring us towards the healing and understanding of our deeper selves.