This year, Nevermind is 30, and it’s still pretty good. It is, at the very least, also eternal. You can’t dispute the artistry. Should I say more? I must, although since few albums are more glorified it’s hard to actually listen to Nirvana with your own ears, which makes sense given they mainly write nursery rhymes. Yet Nevermind is colossal for one major reason - catchiness. If you return to it, you know what you’re getting. Those diamante melodies are undimmed.

Year after year, it remains more than artefact: it is a living symbol of attainment. Post-grunge was merely the beginning of a Platonic quest for palatable dirt. Nevermind’s relentless simplicity has inspired everyone from Post Malone (whose Nirvana covers could’ve launched a summer dress campaign) to Lil Peep, Lana Del Ray and Machine Gun Kelly. Punk and metal may have birthed Nevermind, but pop has received the fruits of its labour - demanding, clean rage, outsider music that’s raiding the skybox at a football game. In a stroke, the album legitimised college rock, aestheticised it and tossed off choruses that can make anyone feel included. That is, alone, extraordinary.

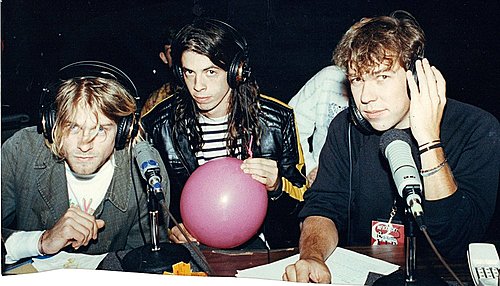

I don’t think many people who made the record knew what they were doing beyond their very best at the mic or mixing desk. Nevermind just had to be blunt and destructive. Kurt, Dave and Krist didn’t want to lose their influences, the punk and the Creedence Clearwater, a mesh of manners. “That’s one of the reasons Kurt wanted the record to sound heavy,” producer Butch Vig told VH1’s Classic Albums series, “because he knew the songs were really hooky, really poppy [...] so if the guitars are roaring and really thick, and the drums are pounding, that dichotomy would work for them.” Geffen had already booked the band into Sound City Studios, heralded for the mighty forging of Fleetwood Mac’s Fleetwood Mac with five-second echo decay. He’d heard Bleach, the group’s debut, and thought it needed more beef, less gristle. Cobain sent him a tape of their new material a week before they were due to meet in L.A. “You could barely make out anything,” Vig would say in 2016, “but I could hear the start to ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit,’ and could tell it was amazing.” They played it for him first as a warm-up. The producer could only swallow his shock and ask, would they play it again? No need for rehearsals. They recorded seven songs in five days.

However, Kurt began to drag his feet, agonising over multi-tracked guitars and writing lyrics with minutes to spare before the tape rolled. Dave Grohl and Krist Noveselic would often finish their parts several days before he got round to them. Kurt polished and double-tracked and overdubbed. Depending on who you ask, he was cajoled, tricked or hen-pecked into harmonies, but I reckon the man himself was more culpable than he let on. His voice, that melodious howl, deserved a power wash.

Enter Andy Wallace, a young engineer who’d made his name with Slayer, easy on the reverb and EQ. Vig’s original mix was scrapped, but not forever. It is more organic. Everything’s looser, though not by much - these songs embrace rigidity. Neither mix lets much noise off the leash. But the album does feature many guitars - at least five on ‘Drain You’, about the same on ‘Come As You Are’, tightly and carefully laid and bludgeoning, exhaustive. The band clearly wanted to hammer themselves into us. Because as good as Nevermind can be, it is also a bit stiff, performed and mixed with such a singular mind as to what it wants - namely, you don’t forget it fast - that thunderous simplicity wipes so much else off the table. Granted, that’s a huge virtue. It just makes the album less playful than it might’ve been, and arguably puts Nevermind in the rarefied company of albums that are easy to stick on but hard to look forward to.

Nirvana’s contemporaries were doing far more interesting things with noise, nihilism and savagery. The band couldn’t out-fuck them. But they could write anthems. You can hear it in earlier material like ‘Negative Creep’, ‘Swap Meet’ and ‘About A Girl’; with older drummer, Chad Channing, they’re doing everything possible to accentuate inevitability. Dave Grohl is famed for his caveman wallops and crashes, but he copied many of Channing’s rhythms beat for beat - the same rhythms that built the band’s April 1990 sessions, a dry run for the album. When they poached Grohl, they just gained more volume and precision. His snare fills are like a herd of wildebeest charging through a valley, leaving no hook unheralded. They are the perfect accompaniment for slamming someone in the head but making sure they know it’s coming.

With bass lines tugging at Nirvana’s root notes - a tic of their punk ethos and, perhaps, Noveselic’s blues - you fall into swift patterns with their music. Songs are instantly memorable yet rarely surprising. Once Nevermind gives you 20 seconds of an idea, you have a good punt at what the next three minutes will sound like. Even when Kurt is screaming his bloody heart out, it’s contained, calculated. Some of the record’s finest moments arise at its messiest - ‘Breed’, for instance, yelling “She said!” a final time with an accentuated D (“She saiddddduh!”) breaking the strict walls of the song’s composition. Or the opening half-minute of ‘Territorial Pissings’ in which a frantic voice seems to address us from a TV screen, demanding we love each other. For a gnarly takedown of macho suppositions, it’s goofy and acerbic, with a filthy guitar riff kicking the glass in.

‘Nameless, Endless’, the hidden track that was actually left off the album’s initial pressings, comes nearest to a freewheeling cacophony. It feels like a jam, a nascent aim at In Utero’s darker, superior stupor two years down the road. Here, you get blasts of unbound personality that characterise Sonic Youth, Hüsker Dü and the true grunge forefathers, Green River: bands for whom colouring outside the lines of foundational melody is just as important as the foundation itself.

Which again, isn’t to say that Nirvana’s slavish exactitude doesn’t deserve the praise it receives. Future rappers like Lil Wayne or Freddie Gibbs may not have given a shit about ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit’ (“I used to listen [to that song] before all my football games,” Gibbs divulged to Complex) if it wasn’t so crisp and well-honed. Mums wouldn’t have played ‘In Bloom’ in the car on the school run if they couldn’t hear all the words. And the album is frequently cathartic; you can headbang to “He’s the one who likes all our pretty songs” forever, stopping to extract a thread of sweat-swept hair from your Red Stripe.

However, you may thirst for more surprises. Nevermind’s simplicity makes it eternal, but also eternally samey. The quiet-loud dynamism, obligatory in any review lest Rolling Stone’s David Fricke belts me in the nuts, rolls out the same trick over and over. Guitar solos are inevitably a variation on the vocals or too shit to mention. Kurt’s drawl strides up a couple of notes, then down. Hisses erupt from either side of the bridge to ‘Drain You’, but we end right where we started, wearing a t-shirt that reads, I came for the hooks, and boy, did I come early!

The quiet moments that are merely quiet, such as ‘Polly’ and ‘Something In The Way’, are refreshing. The first features one of the album’s most inspired gaffes, where Cobain sings, “Polly said . . .” a little early on the third verse, something he didn’t mean to do but worked into the track’s sinister perspective on an animalized rape-murder victim. As Bob Dylan once remarked upon listening to it, “That kid has soul.”

‘Something In The Way’, meanwhile, stands apart as a hymn to the Nirvana frontman’s bouts of homelessness, the detritus of bridge kippers and bad liquor, a time in his life when he’d sleep in the hotel rooms he was meant to be cleaning for $3.50 an hour or whatever ludicrous wage he put up with. The whispers, cello and exhaled mystery of the chorus - are we meant to hear this as utterly broken or comfortably resigned? - give Nevermind more texture.

Yet there are diminishing returns to cuts like ‘Lithium’ and ‘In Bloom’ that don’t strike on soft ground or mash you in the face. The album is mediocre when, ‘. . . Teen Spirit’ aside, it’s reaching for the rafters, neither fast nor slow, demanding a raised fist. Rock clubs advertising All The Hits are going to play these tracks forever. Grunge came to be defined by them - the anthemic apathy, the mid-tempo crunch - which is less of a problem if you don’t listen to much rock music. Maybe that’s why mainstream pop and hip-hop embrace the album so warmly: it has the veneer of heaviness and hard truths while only rarely sounding dangerous.

As Layne Staley, another Seattle icon, would say of his own time with Alice In Chains, “There’s no huge, deep message in any of the songs. We recorded a few months of being human.” Nevermind, likewise, is a project that continues to resist critical theory with the fact that it is what it is, unpretentiously so, and only wants to help kids lose their shoes together. It came at the right moment to blow raspberries, watch TV, goof off on a railroad, suggest that apathy and tartan on a fag-burned sofa are the smartest form of rebellion. But equally, it’s just good fun - a compact, eager-to-please record that pins a wobbly smiley face on self-hatred. Nevermind will continue to be a rite of passage for teenagers or anyone who likes hard feelings swiftly boxed; a call for mini moshers, like those at the band’s Leeds Polytechnic show, to take their turn diving into acceptance.